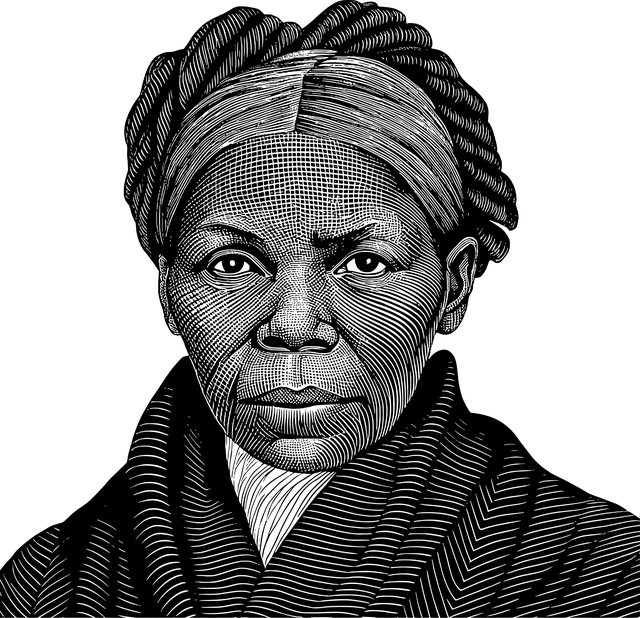

As part of the Historical Society of Moorestown’s New Jersey Speaks Lecture Series, historical reenactor Dr. Daisy Century portrayed Harriet Tubman for residents at the library on Feb. 18.

Century is an acclaimed actor, historian and recognized Smithsonian Institution performer who considers Tubman her role model, someone who encouraged her to put others first and lead by example. A historical interpreter, Century’s characters include entrepreneur and philanthropist Madam C.J. Walker; abolitionist Sojourner Truth; writer Phyllis Wheatley; aviator Bessie Coleman; mail carrier Mary Fields; and Cathay Williams, the first African American woman to enlist in the U.S. Army. She fought during part of the Indian Wars while disguised as a man.

Century is also an educator and writer, having taught for more than 20 years in the Philadelphia school system as an award-winning science teacher.

“What made her (Tubman) so iconic, so revered?” Century asked. “Number one, her track record. She made it all the way from the Maryland Eastern shores to Philadelphia in her late 20s by herself, and she kept going back with compassion in her heart for other people. Anybody that did that, I would want to go with her.”

Century explained that Tubman was a scientist who specialized in many areas. She was an ornithologist – a person who studies birds – and knew their calls. She also understood their tracks and knew that when they flew through the forest, if they were louder than usual, the birds would direct Tubman’s secret travels.

Tubman was also an environmentalist. She knew all about the layout of the land and how to cross rivers when they were high or shallow, and knew hills and valleys. Tubman also dabbled in astronomy and knew all about the night sky. She understood when the moon was full, Century explained, avoiding travel because of too much light. She told time by when the sun rose and when it set.

“Next, she was a botanist (a person who studies plant life),” Century noted. “She knew all about the plants that were good for itching and swelling. She knew what plants were good for an upset stomach. She knew what plants to dig up to eat the roots of along the way.

“Harriet Tubman was clever and smart, very smart, and she had a lot of compassion in her heart.”

Born as Araminta “Minty” Ross in 1822, Tubman was put into labor early, and by the age of 10, was hired out as a woodcutter, pest trapper and field worker. After being struck on the head with a large iron weight, she began suffering from severe headaches and a chronic sleep disorder called narcolepsy, according to the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

After marrying John Tubman while still a slave, Tubman yearned for freedom, and on Sept. 17, 1849, she and her two brothers, Ben and Henry, set out to escape their Maryland plantation by heading north. The men soon turned back, but Tubman completed the nearly 100-mile journey to Philadelphia with the help of the Underground Railroad.

Between 1850 and 1860, Tubman made more than a dozen journeys across the Mason-Dixon line, guiding family and friends from slavery to freedom. Her role as captain earned her the nickname “Moses,” after the religious leader, and through her friendship with fellow abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass, Tubman created her own network within the Underground Railroad.

After a decade as a conductor, she was called to action when the Civil War began in 1861. After just two years of service, Tubman was tasked with moving behind enemy lines to gather intelligence from a web of informants. First a nurse, laundress and cook, now a spy and scout, Tubman became the first woman in history to lead a military expedition in 1863, when she guided Black troops in the Combahee River Raid in South Carolina.

After the Civil War, Tubman lived on land she owned in Auburn, New York. She was married for the second time to former enslaved man and war veteran Nelson Davis in 1869, and a few years later, they adopted a little girl named Gertie. Tubman remained illiterate, but traveled parts of the Northeast to promote women’s suffrage with the one of the movement’s leaders, Susan B. Anthony.

Tubman was 91 when she died of pneumonia in 1913, but her legacy lives on.

“Harriet Tubman wasn’t scared of (anything),” Century pointed out. “She wasn’t scared of (anybody). She didn’t come into this world to be (a) slave, and she didn’t stay one … Early one morning, she strolled away. She ran to the forest, she ran through the forest. She ran and ran. She ran from the streams, she swam through the streams …

“She ran and ran and ran until she got to freedom, but she didn’t stop there,” Century added. “She kept going back time and time again.”